Alexandria (the one in Egypt, to be specific) was one of the greatest cities in the ancient world, but shrunk in both size and prestige after the Arab conquest of Egypt, when the Egyptian capital was moved first to Fustat and then to Cairo (which today has grown so large as to have swallowed the remains of nearby Fustat). It was rebuilt starting in the 19th century and today is one of the 50 or 100 largest cities in the world, depending on how you measure urban population. It was the first stop on my trip to Egypt, after flying into Cairo during a sandstorm and then driving all night to get to a drafty apartment in a cool, rainy city. It was January, but I was packed for Cairo and Luxor weather, so I was totally unprepared for the Alexandrian weather and had to go buy a jacket the next day, and to get a room at a decent hotel where the wind wasn’t blowing in every night.

Alexandria is incredibly unique, a Greco-Roman outpost in the middle of a country that is otherwise Arab or Pharaonic, but the Greco-Romanness of the ancient city was definitely affected by Egyptian culture. I don’t mind saying that the first mummy I saw in the Alexandrian museum, wrapped up like a mummy should be but with a painted Greek face on it where the carved Egyptian funerary mask should’ve been, weirded me out a little bit.

The mummy in question.

The first site I checked out was the amphitheater. I always dig a good amphitheater:

The amphitheatre, very well-preserved, wasn’t rediscovered until the mid-20th century

More of the amphitheater complex; one of the things I like about Egypt are the scenes of ancient and medieval sites existing within a totally modern, urban space.

The “Villa of the Birds” is near the amphitheater and is so named for one of the mosaics still preserved there:

Villa of the Birds, yes?

A trip through the city’s catacombs followed, which was awesome but for which I’ve basically got zilch in the way of decent pictures. Digital camera tech was considerably more primitive back then.

Later I headed to the harbor, the geographic feature that made and still makes Alexandria such an important city. In ancient times the shore of the harbor was dominated by the great Lighthouse of Alexandria, but a series of earthquakes brought her down, and in 1477 the ruins were used by the Mamluk Sultan Qaitbay to construct a massive fortress, the Citadel of Qaitbay, to defend the harbor.

Fort Qaitbey, the entrance

View of the harbor from the top of the fort.

View of the harbor entrance.

Near the Citadel is the Mosque of Abu al-Abbas al-Mursi, a famous 13th century Sufi whose remains are said to be interred there. For reasons that escape me now, all these years later, I didn’t get particularly close to this mosque and just took a photo of the minarets and domes at some distance.

El-Mursi Mosque

The last stop in Alexandria was the Montaza Palace and Park, built and expanded in the early 20 century by the khedives (who later styled themselves “kings”) as a summer palace and hunting lodge. It’s situated on a bay, and the whole combination of bay, gardens, and palace is very striking.

Montaza Palace

Montaza Gardens

Montaza Bay

The Foreign Exchanges Companion

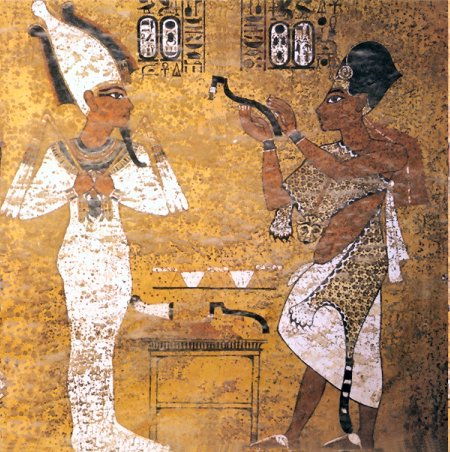

King Tut…I don’t trust the guy…something about the way he’s looking at Ay in this tomb painting, though admittedly he would’ve been dead at this point

King Tut…I don’t trust the guy…something about the way he’s looking at Ay in this tomb painting, though admittedly he would’ve been dead at this point